RELATIONS AMONG LONG TERM TRENDS OF

RELATIONS AMONG LONG TERM TRENDS OF

PRODUCTIVITY , ECONOMIC GROWTH,

TRADE DEFICIT AND JOBS IN USA

by

Chih Kwan Chen

(June 30, 2004)

Abstract

The correlation between the long term trends of productivity gain and US

economic

growth is studied by stripping away wide gyrations due to the economic

booms and

busts from both sets of data. For the preglobalization era, a strong positive

correlation

is observed as expected. However, in the current globalization phase the

positive

correlation has changed to a negative one, implying that higher productivity

gain

rather induces slower economic growth. This surprising outcome is further

traced

down to the long term trend of increasing US trade deficit that undermines

the long

term potential of job creation due to both the forced automation and offshore

job

outsorcing in order for US domestic industries to compete with foreign

rivals.

1. Introduction

It is often claimed that the productivity

gain drives the economic growth. In this paper we will study the validity

of this claim. First of all we must know what are the "productivity gain"

and the "economic growth" mentioned in the phrase. Most people think that

they are just statistics released by the government every quarter. In the

next section we will show that the jumpy annual data (don't need to mention

the quarterly data) can not be reconciled with the claim that the productivity

gain drives the real GDP growth. Actually what we should study and the

opening claim is refering to are the long term trends of the rate of productivity

gain and the long term real GDP growth rate that are buried beneath the

widely gyrating annual data pushed around by economic ups and downs and

need a careful analysis to reveal.

Section 3 is devoted to the detailed

study of the long term trends of productivity gain rate and real GDP growth

rate, and the relation between those two data sets. During the preglobalization

era, that is, before Reagan era, there exists a strong positive correlation

between the two data sets. However, in the current globalization phase,

this positive correlation has turned into a negative one.

The surprising negative correlation

discovered in Section 3 is further analysed in Section 4. There is a strong

indication that the negative correlation is the result of long term trend

of expanding trade deficit that has damaged the long term potential of

the society of USA to create jobs and thus reducing the long term growth

potential of the economy.

2. Uncovering the long term trends of productivity gains

We start the analysis by listing

the mechanisms that can produce gyrations in the annual data of productivity

gain rate.

Mechanism 1: At the top of an economic boom, most people, including

corporate managers, are extremely optimistic about the

continuation of the economic boom. Corporate managers will hire large number

of workers to gear up their

production in order to meet the expected ever surging demands of their

products. Then the boom peaks out,

the growth of sales stagnate, and the productivity of corporations plunges.

When it becomes obvious to

most people that the peak of the economic boom has passed, corporate managers

will panick and start

to lay off workers. As the race between the layoff and the falling sales

heats up, the productivity gain rate will

arrest its sharp fall and eventually hits the bottom. As economy starts

to recover, most people, including the

corporate managers, will be skeptical, and the corporations will not start

to hire new workers. As sales pick

up, corporate managers will drive their bare bone work force to work to

full capacity to meet the surging

demand. Thus productivity will raise rapidly ahead of the real economic

recovery. This kind of gyrations in

productivity gain rate, if plotted on a graph, will look like preceeding

the graph of real GDP growth rate.

However, as is obvious from the explanation, it is the economic booms and

busts that are driving the gyrations

of this kind of productivity gain rate, not the other way around as required

in the phrase that the productivity

gain drives the economic growth.

Mechanism 2: As an economic boom proceeds, corporations will put their

idle capacity back to the production lines. The

natural way to do is to put the most efficient capacity among the idled

back to service first. Thus as economic

boom matures and the sales growth slows, so are the productivity gains.

When sales growth turns to negative,

capacities employed in the production lines need to be idled. This will

be done by idling the least efficient

capacity first. Thus as the sales growth turns to negative, the productivity

gains rate will turn to positive and

rises. The productivity gain curve from this mechanism also will lead the

curve of annual growth rate of real

GDP. From the explanation it should also be obvious that it is the economic

ups and downs that is driving this

mechanism of productivity gains, not the other way around as required in

the phrase.

Mechanism 3: During an economic expansion, corporate managers have a

natural tendency to want to invest in new

technologies to improve the efficiency of their productions. However, it

takes time to bring those new

technologies into real production, so the productivity gains from this

mechanism will lag behind the curve of the

annual growth rate of real GDP. The productivity gains of this mechanism

apparently can induce higher

economic growth in future and belongs to the category that we want to study.

There are other mechanisms of productivity gains, and they will be discussed

later in appropriate places since they will not cause wild gyrations in

the productivity gain curve.

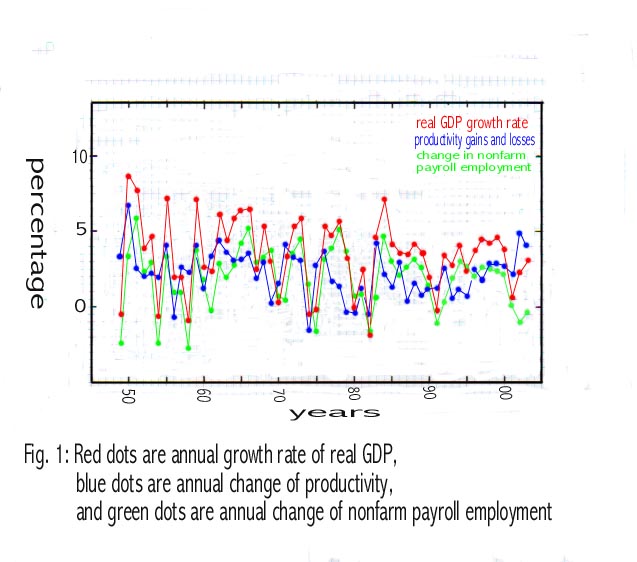

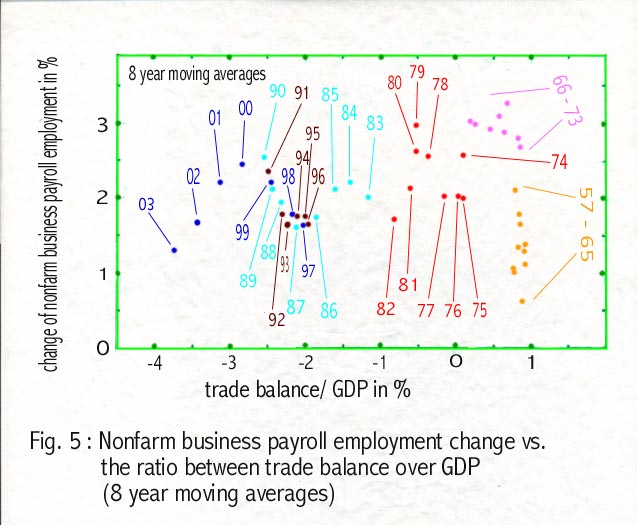

Now let us look at the actual data

themselves. The annual growth rate of real GDP from 1949 to 2003 (Ref.

1) are plotted as red dots, the annual growth rate of productivity (Ref.

2) as blue dots, and the annual growth rate of nonfarm payroll employment

rate (Ref. 2) as green dots in Fig. 1 respectively. By a close inspection

of the red dots and the blue dots we will

see that the blue curve has a tendency to fall first when the red curve

is still hanging on at the high ground. This is a clear indication that

the blue curve, the productivity gain, preceeds the red one, the real GDP

growth. This is an indication of the domination of Mechanisms 1 and 2 in

the gyrations of the productivity gain curve in Fig, 1as discussed above.

Thus we need to eliminate the wide gyrations present in Fig. 1 in order

to study the underlying long term trends of the data. The green curve,

the change of nonfarm payroll employment, keeps up well with the real GDP

growth rate, the red curve, except in the period after 1995; this discrepancy

will be discussed later.

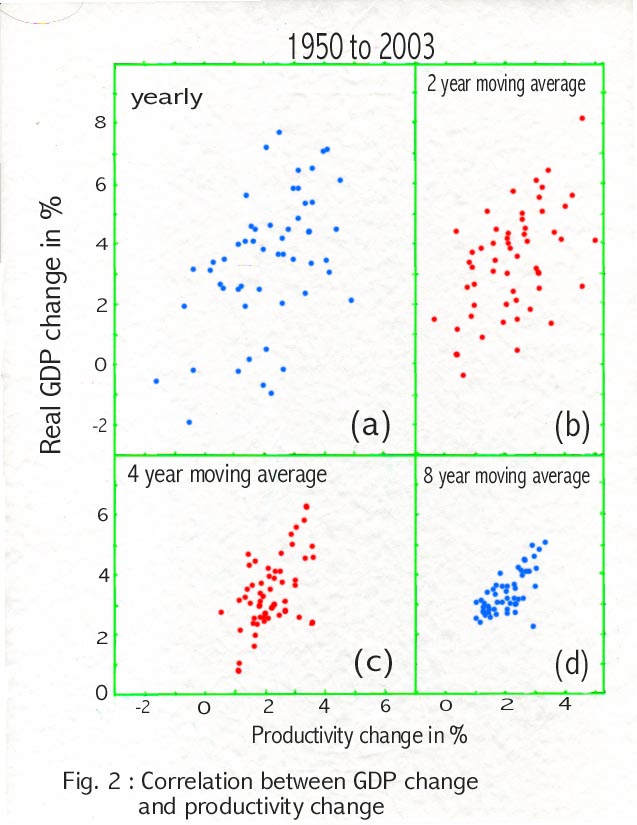

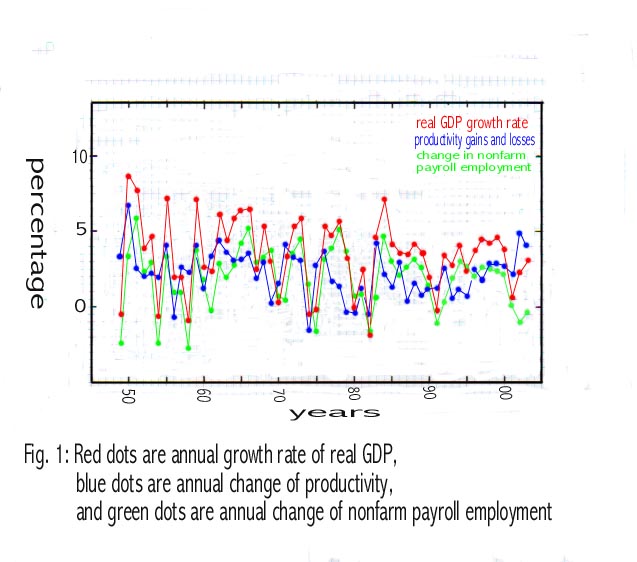

The annual data of productivity

gain and real GDP growth rate are plotted in the style of a correlation

graph in

Fig. 2 (a). The correlation there is rather poor as expected. By taking

2 year moving averages of both data sets as in

Fig. 2(b), the positive correlation becomes unmistakable,

whereas gyrations from one data point to the next is reduced somewhat.

By going into 4 year moving averages as in Fig. 2(c), the positive correlation

is further improved.

With 4 year moving averages the gyrations of both data sets, of course,

are reduced further. Average length of an economic cycle during 1949 to

2003 is longer than 4 years but shorter than 8 years. Thus the gyrations

in 4 year moving averages, that is not presented here, are still due the

ups and downs of economic cycles. To extract the underlying long term trends

buried beneath the economi cycles, correlations between 8 year moving averages

are shown in Fig. 2(d). In principle we can go even longer by taking more

than 8 year moving averages. However, if we go too long, all the resulting

data points will cluster around the center of the correlation graph and

nothing interesting will be revealed. We consider 8 year moving averages

as a good compromise and will regard 8 year moving averages of various

data sets as revealing their long term trends throughout the remainder

of the paper.

3. Correlations in the preglobalization and the globalization phases

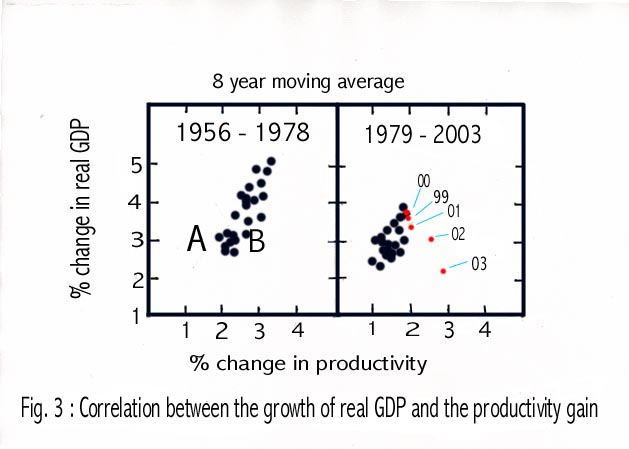

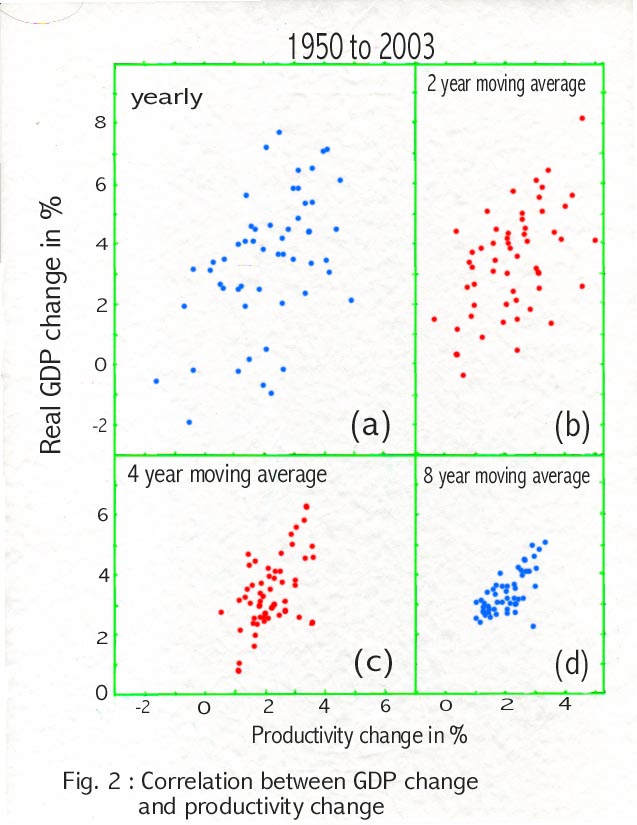

To further analyse the long

term correlations between the productivity gain and the GDP growth, 8 year

moving average data sets are divided into two time periods, from 1956 to

1978 and from 1979 to 2003, and are plotted in Fig. 3. The

graph for the period from 1956 to 1978 shows a clear positive correlation.

We may confidentally conclude that the inovations in technology and the

opening up of new high productivity industries have steadily pushed up

economic growth during that period, and the quote at the beginning of this

article that productivity gain drives economic growth is really refering

to this kind of positive correlation between two data sets.

For the period from 1979 to 2003,

data points from 1979 to 1998 are plotted as black dots, and those of 1999

to 2003 as red dots. As for the black dots, though some kind of positive

correlation still exists, the range of productivity gain becomes much narrower,

from 1% to 2%, compared to the previous period where productivity gains

ranged from 2% to 3%, and consquently the average economic growth is also

lower than the previous period. If superposed on the graph of the period

from 1956 to 1978, black dots in the period of 1979 to 1998 fall into the

region labeled as "A". The productivity gain in the period from 1999 to

2003 has accelerated, but the correlation with the economic growth has

turned into a negative correlation. This means that higher productivity

gain rather has induced lower economic growth; this is totally in contradiction

to the starting phrase to proclaim that productivity gain drives economic

growth. It should be noted that the data points in Fig. 3 are all 8 year

moving averages, thus the data point of 1999 is rather measuring the condition

centered around the year of 1995. The red data points showing the surprising

negative correlation centered around the period of the latter half of 1990's,

supposedly the era of PC and internet. In the next section

we will analyse the cause of this surprising negative correlation revealed

here.

4. The cause of the negative correlation

The most desirable productivity

gain is due to the emergence of highly efficient new industries; this kind

of productivity gain will add to employment and will contribute to economic

growth. The automation of an existing, but rapidly expanding industry will

not cause the loss of jobs so it will also contribute to economic growth.

The automation of a matured industry will result in layoffs; with the total

sales stagnating with or without the automation and less employment as

the consequence of the automation, this kind of productivity gain will

reduce jobs and thus hurt the economic growth. Then there are a kind of

forced automation; a struggling industry undergoes automation to compete

with imported goods manufactured in low labor cost countries. This type

of automation will result in massive layoffs and will definitely hurt the

economic growth.

Besides automation, productivity

will change by moving manufacturing facilities out of the country whereas

moving the facilities within a country from a high wage area to a low wage

area will not change the productivity. To explain this statement, let us

consider the following example: XYZ Co. sales its products to consumers

so that its annual sale of 1 billion dollars is directly tabulated into

GDP as the final sales. It employes 1000 workers, 900 in the manufacturing

facility and 100 in the headquarter. Its manufacturing facility is in a

high wage area. The expenses of XYZ Co. are as follows: 300 million dollars

a year is for the buying of raw material used in the production. To simplify

the argument here, let us assume that all the 300 million dollar raw material

are imported from overseas. The labor cost for the manufacturing is 500

million dollars a year, the expenditure of the headquarter is 100 million

dollars a year, and the profit of XYZ Co. is 100 million dollars a year.

The contribution of XYZ Co. to GDP is 700 million dollars a year since

300 million dollars of imports for the raw material must be subtracted

as net import from its total final sales of 1 billion dollars. Thus the

productivity of XYZ Co. is 700 million dollars divided by 1000 workers,

that is $700,000/worker/per year. Now suppose it lays off 900 factory workers,

move the manufacturing facility to a low wage area within the same country,

rehire 900 workers in the new area, and consequently reduces the labor

cost for manufacturing by 100 million dollars a year. Also let us assume

that XYZ Co. keeps the price of its procducts steady. Thus the profit of

XYZ Co. doubles to 200 million dollars a year. Now for the productivity,

the contribution of XYZ Co. to the final sales category of GDP is still

700 million dollars a year, and the number of workers is still 1000, so

the productivity of XYZ Co. does not change. Suppose XYZ Co. outsources

its manufacturing facility to a developing nation. The labor cost in the

new host country is now only 200 million dollars a year. Suppose that XYZ

Co. still keeps the price of its products at the same level. The profit

of XYZ Co. becomes 400 million dollars a year. How about its productivity?

Since XYZ Co. must reimport 500 million dollar worth of products to be

sold to the consumers in this country, its contribution to GDP is reduced

to 1 billion dollars - 500 million dollars = 500 million dollars. Its domestic

workforce consists of 100 workers in the headquarter, so its productivity

is now 500 million dollars divided by 100 workers = 5 million dollars/worker/year.

Thus the productivity of XYZ Co. jumps almost 7 folds by just moving its

manufacturing facility outside of the country.

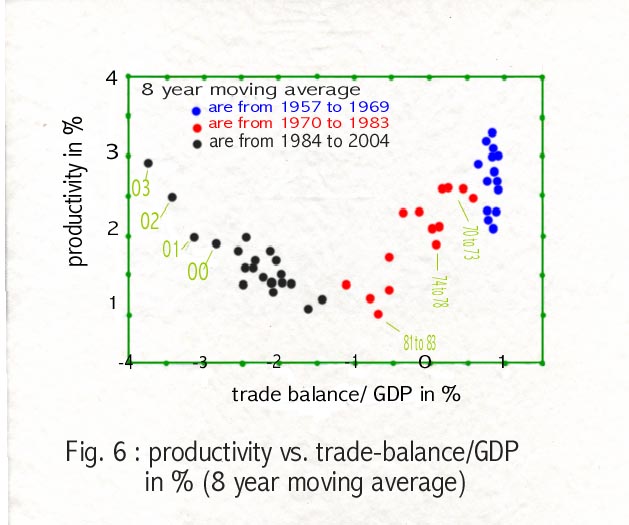

As clear from the above discussion

we suspect that it is the run away trade deficit that is boosting the productivity

by forcing many struggling domestic industries into automation in order

to compete with inexpensive imports and inducing many to outsource their

not very high tech manufacturing facilities to low labor cost countries;

this kind of activity, though boost productivity sharply, will erode the

long term job creation potential of this country and thus reduces the long

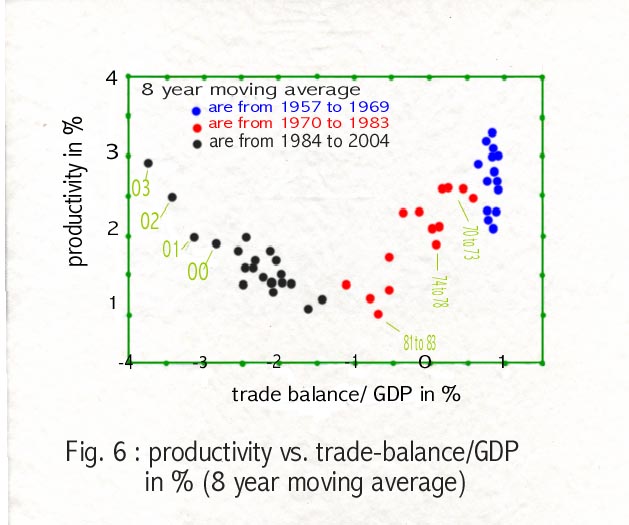

term economic growth as we observed in the red dots of Fig. 3. To confirm

this suspicion, 8 year moving averages of the ratio of merchandise trade

deficit over nominal GDP are plotted versus 8 year moving averages of the

productivity gain in Fig. 4. Various periods are plotted with

different colors. The blue dots are for the period from 1957 to 1969;

during this period USA had a merchandise trade surplus about 1 % of GDP,

and the productivity gains scattered around from 2% to 3%, indicating the

lack of correlation between those two data sets. Red dots are from 1970

to 1983. There is a broad trend that larger the trade deficit, lower the

productivity gain. However, a close inspection reveals that the red dots

are grouped into three clusters and with two huge gaps separating the clusters.

Two gaps between the clusters of red dots correspond to two energy crises.

When oil price jumps, trade deficit will explode. However, trade deficit

expansion due to commodity price jump will hurt the economy and lower the

productivity gains, not like the trade deficit based on the manufactured

goods that will in general boost consumption and stimulate economic growth

(Ref. 3 and 4 ). The black dots are for the period from 1984 to 2003;

a strong correlation between the rising productivity and the expanding

trade deficit is clearly displayed. Most of the black dots not labeled

correspond to black dots of the section 1979 to 2003 of Fig. 3. The black

dots from 2000 to 2003 correspond to red dots in Fig.3 and are the ones

forming the negative correlation between the long term productivity gain

and the long term economic growth. The points after 2000 are showing a

much stronger correlation between the productivity gain and the expansion

of the merchandise trade deficit.

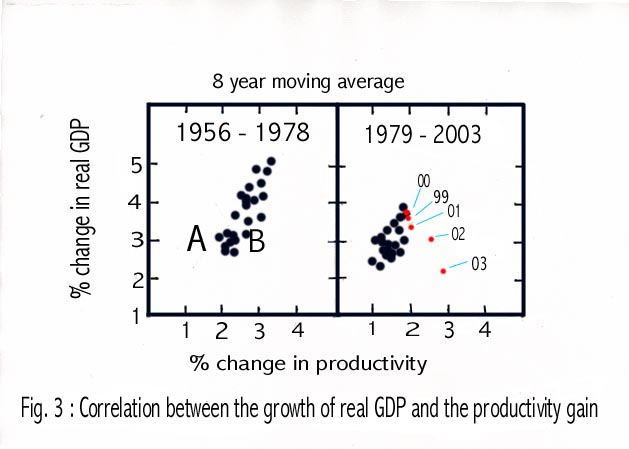

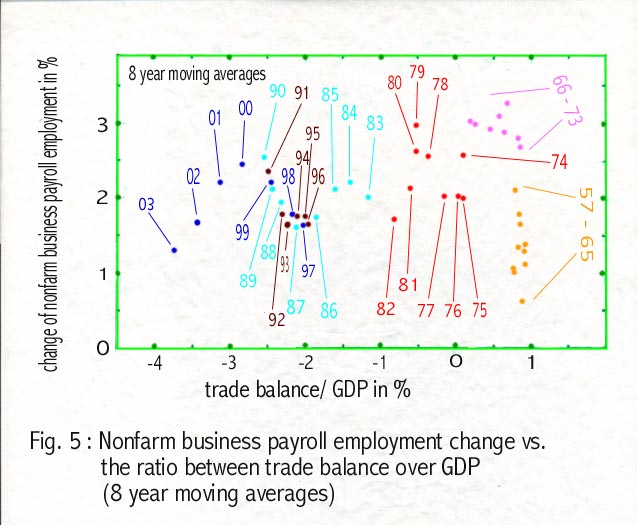

In Fig. 5, 8 year moving

averages of yearly changes in nonfarm business payroll employment are plotted

against 8 year moving averages of the ratio between the merchandise trade

deficit and the nominal GDP. Various periods are tagged with different

colors and with explicit labellings. Here we direct the attention only

to the blue dots labeled from 97 to 03.

At first within the period of blue dots the rise of productivity and

the rise of job creation potential went hand in hand, indicating that the

opening up of new industries, that is, reflecting the proliferation of

PC and the emergence of internet society, has created many new jobs more

than compensating the job loss due to the steadily expanding merchandise

trade deficit. However, as 8 year moving averages of trade deficit ratio

moves above 3% of GDP, the erosion of job creation power is clearly

displayed. In calculating 8 year moving average of the coming dot of 2004

we need to subtract the number of jobs created in 1996 and add the number

of jobs created in 2004 to the sum of jobs from 1996 to 2003. In 1996 totally

2.4 million jobs were created. If the jobs created in 2004 is less than

2.4 million, then the job creation ratio will certainly drop further. On

the other hand the trade deficit ratio will move toward 5%. This means

that the 2004 dot will slide down the curve toward the lower left corner

further. Considering the numbers of jobs created in 1997, 1998, 1999 and

2000 are all around 3 million, the slide down of future blue dots along

the curve toward the lower left corner of Fig. 5 will probably continue

for quite a while.

4. Conclusion

The observed negative correlation

between the long term trend of productivity gain and that of economic growth

in recent years is traced down to the rapidly expanding merchandise trade

deficit of USA. The run away trade deficit is causing the rapid rise of

the long term productivity gain through forced automation and offshore

job outsourcing, but is steadily eroding the long term job creation potential

of the society and is causing the decline of the potential of the long

term economic growth.

References

1. Bureau of Labor Statistics

2. Bureau of Economic Analysis

3. Article No. 1 posted on this

website

4. Article No. 2 posted on this

website